culture

Tropical Sublime: Tarsila do Amaral at MoMA

Tarsila do Amaral, the foundational figure of Brazilian Modernism, occupies the second floor of MoMA with lush and alluring paintings in her first-ever solo exhibition in the US.

- By Gisela Gueiros

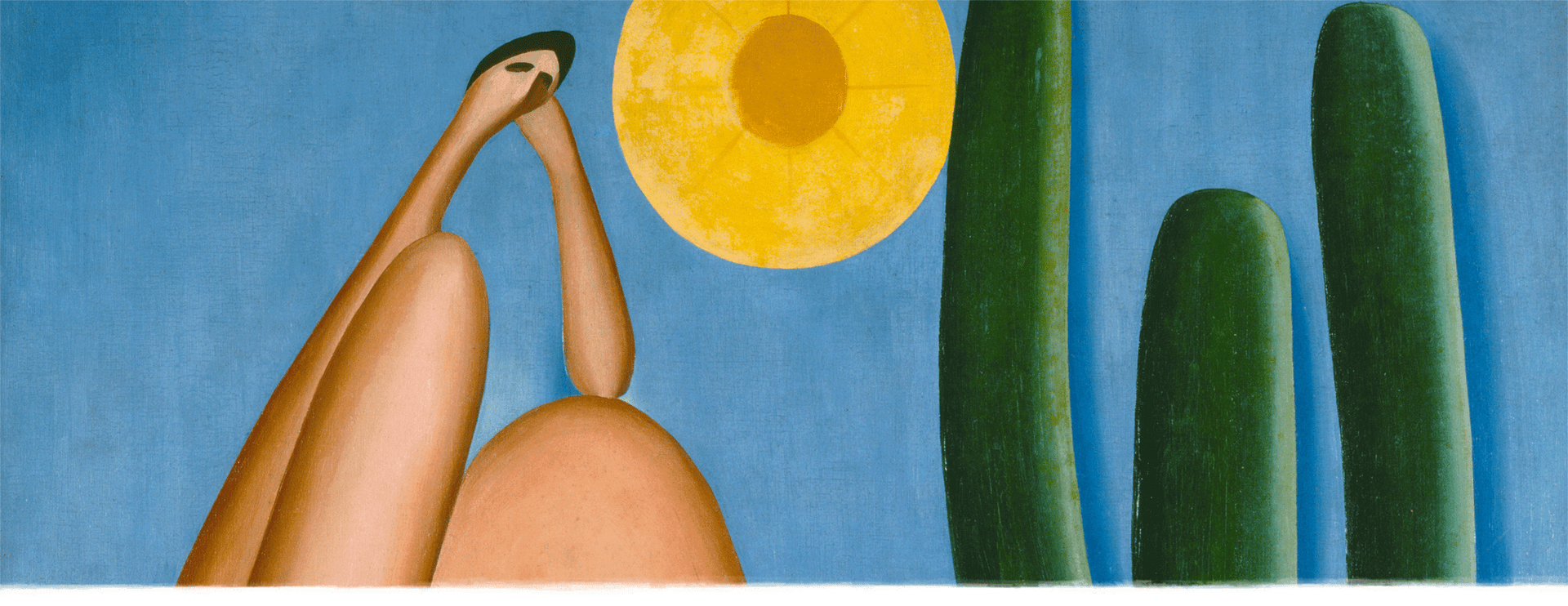

Like Frida (Kahlo) in Mexico, Brazilians grew up on a first-name basis with our most celebrated painter. To this day, 45 years after her death, “Tarsila" is all you need to say for instant recognition. Born in 1886 in São Paulo, Tarsila left for Paris in 1920 – she considered the art education in Brazil too traditional. In France, she studied with artist Fernand Léger at the famous Académie Julian. During this period, which she referred to as her “military service in Cubism”, Tarsila honed the sensuous cylindrical shapes that became her characteristic forms to depict both human and animal bodies, as well as trees and plants.

The MoMA show leans strongly towards the earlier part of her career, the 1920s and 30s, when she established herself as a central figure in the development of modernism in Brazil. The exhibition includes a wealth of archival sketchbooks, drawings and archival photographs, but it is the large scale, exuberant canvases that seize hold of your attention. Brightly colored, depicting exotic creatures, oddly shaped bodies and magical landscapes, her work from this period is a remarkable synthesis of an international arts education with the sultry, tropical influences of her home, revealing touches of vernacular architecture and Brazilian folk references, such as Saci Pererê and Cuca. Her work pulsates with Brazil’s energy and vibrant nature.

Her most iconic painting, “Abaporu” from 1928 shown as the main image in this blog post, is given center stage in the exhibition and features a distorted figure alone in a spare landscape with a single cactus. The title, borrowed from a Brazilian indigenous language, “aba” plus “poru”, means the man who eats human flesh. Painted as gift to her husband, the poet Oswald de Andrade, the image became the visual representation for a pivotal artistic movement in Brazil, the Anthropophagic Movement, that posited a Brazilian culture that literally “ate” its influences, as if consuming human flesh. The Manifesto Antrofágico (the Cannibalist Manifesto) was published that same year and is considered the seminal text of Brazilian modernism. The text was an answer to Brazil’s colonial trauma and suggested that an autonomous national modernism could be achieved by embracing local influences – and metaphorically eating “the other”.

Towards the end of the 1930s, and in later phases not covered in this MoMA retrospective, Tarsila becomes even more political as an artist. The last painting in the show, “Workers” from 1933, is the largest she ever made – and symbolizes this socially conscious period. It portrays a sea of workers faces floating in front of a factory and its smokestacks. The faces, male and female, and a variety of races, are just as emblematic of Brazil as the flora and fauna of her earlier works.

There has been a veritable love affair in recent years between Brazilian art and New York museums – an incredible number of retrospectives of influential Brazilian artists have appeared in major institutions: in 2014, with Lygia Clark and her interactive foldable metal critters at MoMA; and 2017 with Lygia Pape and her participative performances at the MetBreur, and Hélio Oiticica's fabulously immersive environments at the Whitney.

With this triumphant exhibition of Tarsila’s work, we now can trace the roots of where these younger artists all came from. It was Tarsila who is most responsible for laying the foundations for Brazilian art. The show is a delight and a wonderful reminder of art beyond the western cultures. It makes Brazilians very proud!

Enjoy Tarsila do Amaral at The Museum of Modern Art through June 3, 2018.